Why should I always switch doors in the Monty Hall problem?

You’re facing three closed doors. Behind one of them a prize you cherish – a seed phrase for one bitcoin – and behind the other two, broken bricks. Monty Hall tells you to choose any door. Regardless of your choice, Mr. Hall will open one of the doors containing broken bricks and will give you the option to switch doors, if you wish. Should you? The answer is yes.

Because chances are now 50-50. Right?

Wrong. By switching doors, your chances of picking the bitcoin actually increase to \(2/3\), or approximately \(66%\). Many statisticians encounter this problem in introductory courses on conditional probability but a lot of people never heard of it and find it a curious and tricky challenge. Most people I know get it wrong and struggle to understand why.

Visualising it

Ok. You may not be convinced. It’s fine. Totally fine. Maybe you won’t even bother seeing the theoretical aspects and proof based on the Bayes’ rule later on this post and will close the tab right after this section. Also fine. Through the code snipped below, 10,000 games were simulated using Python (link to the Colab Notebook).

import numpy as np

class MontyHall:

def __init__(self, change=False):

self._max_simulations = 5000

self._change = change

self.iteration = 1

self.wins = []

self.losses = []

self.win_pct = []

self.loss_pct = []

def win(self):

self.wins.append(1)

self.losses.append(0)

def loss(self):

self.losses.append(1)

self.wins.append(0)

def simulate(self):

while self.iteration < self._max_simulations:

doors = np.array(["bitcoin", "brick", "brick"])

np.random.shuffle(doors)

participant_pick = np.random.randint(3)

if self._change:

if doors[participant_pick] == "brick":

# Brick door chosen, Monty Hall shows one of the brick doors,

# participant switches and then picks bitcoin

self.win()

else:

# Bitcoin initially chosen, participant picks something else

self.loss()

else:

# Sticks to the original choice

if doors[participant_pick] == "bitcoin":

self.win()

else:

self.loss()

self.win_pct.append(np.sum(self.wins) / self.iteration)

self.loss_pct.append(np.sum(self.losses) / self.iteration)

self.iteration += 1

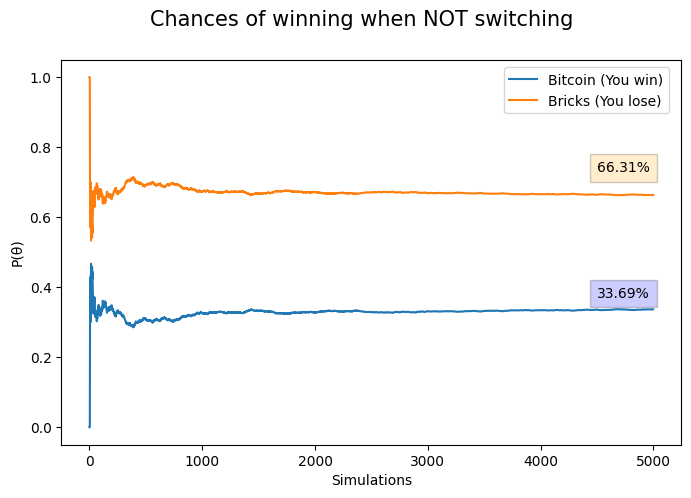

First round of \(5,000\) simulations.

Here the player always keep its initial choice, never switching doors after seeing one of the unfortunate doors revealed by Monty Hall:

As we can see, you are more likely to lose if you don’t switch.

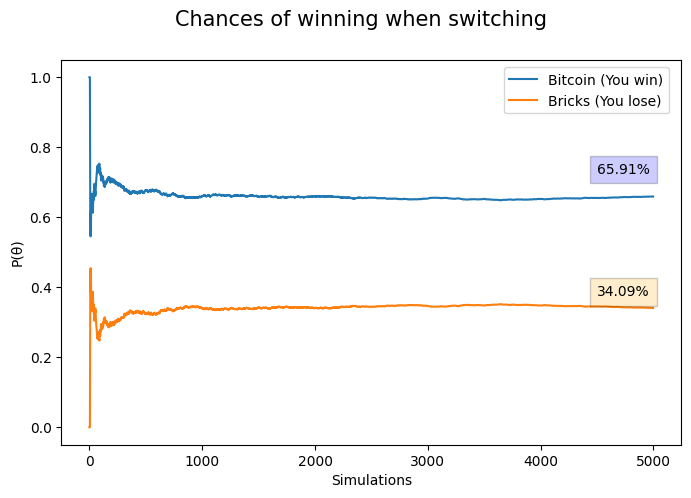

Then, in the next \(5,000\) simulations, the player always switches after Monty Hall’s revelation:

Conclusion

We can empirically see that it’s always better to switch doors.

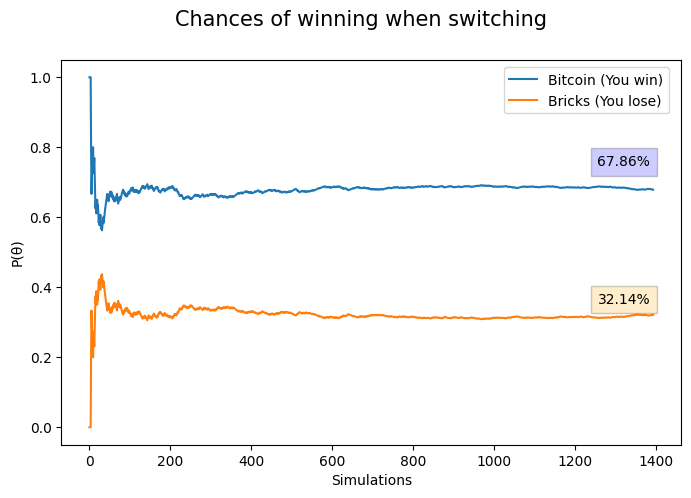

There are always skeptical people who may say this doesn’t prove anything because a single individual can’t play \(5,000\) times… but that’s not how this works at all. We need to extrapolate over a large (infinite) number of trials to reach this empirical proof. If you toss a fair a coin \(5\) times, it may end up facing heads \(4\) times. Maybe. By chance. But over \(100\), \(1,000\), \(10,000\)… over infinite trials the number of heads should be significantly close to \(50%\), otherwise the coin might be biased (purists, go away! Don’t come with the “a coin flip is a deterministic physical process, subject to the physical laws of motion” just yet). Just for the sake of curiosity and ignoring some more complex theoretical aspects, let’s re-run the experiment for the 1.395 episodes of Monty Hall between the years of 1963 and 1976 (not that this actually changes anything I’ve written before… this is completely irrelevant!).

Pretty much the same.

Consider Bayes’ rule.

I assume you have some basic understanding about probability. Everything here will follow basic rules. There’s a nice and quick refresher here.

\(B\) denotes the hypothesis that the bitcoin is behind a specific door. \(D\) is for whichever door the host can open. More specifically, \(P(B=i)\) is the prior knowledge we have about the prize being behind any these 3 doors: when the game starts, the prize could be behind any door with equal chances. So \(P(B=1)=P(B=2)=P(B=3)\). Hence, \(P(B) = \frac{1}{3}\).

During the game there are a few scenarios for the unfortunate doors. What if you choose door 1 and the prize is really behind door 1? Then Monty Hall will not reveal what is behind door 1 and will open doors 2 or 3 arbitrarily and at random, picking one of them with equal chances.

That is \(P(D \mid B) = \frac{1}{2}\), meaning that the likelihood of the host revealing the content of any other door other than that of the prize is 50%.

We will distil this below. Stay with me.

Let the game begin!

You are on stage, 3 doors in front of you, you have no idea where the prize is. Monty Hall asks you which door you want to pick. You make your choice: door 1. Monty Hall slowly walks to the door he’s going to open. Three things can happen now:

- The host can open door 2 or door 3 if the prize is behind door 1; $$P(D=2 \mid B=1) = \frac{1}{2}, P(D=3 \mid B=1) = \frac{1}{2}$$

- The host will not open door 2 if the prize is behind door 2, and will definitely open the remaining door, door 3; $$P(D=2 \mid B=2) = 0, P(D=3 \mid B=2) = 1$$

- The host will not open door 3 if the prize is behind door 3, and will definitely open the remaining door, door 2; $$P(D=2 \mid B=3) = 1, P(D=3 \mid B=3) = 0$$

Monty Hall walks towards door 2 and opens it. Obviously the bitcoin is not here. We now have our denominator based on the marginalisation – sum of all scenarios – over door 2. Hence, \(P(D)\) is given as \(P(D=2) = P(D=2 \mid B=1)P(B=1) + P(D=2 \mid B=2)P(B=2) + P(D=2 \mid B=3)P(B=3)\) which, from the above, is the same as \(\frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{3} + 0 \times \frac{1}{3} + 1 \times \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{2}\). These values are described above. For example, \(P(B=1) = \frac{1}{3}\), \(P(D=2 \mid B=2) = 0\), \(P(D=2 \mid B=1) = \frac{1}{2}\), etc…

Monty Hall then looks back at you at you and asks if you want to switch to door 3 or remain with door 1. You quickly think about the final form of the Bayes rule to reason about the scenarios based on your original choice and the door revealed.

- “The probability that the prize is behind door 1, original choice, given that the host opened door 2”

- “The probability that the prize is behind door 3 given that Monty Hall opened door 2”

- “The probability that the prize is behind door 2 given that Monty Hall opened door 2”

Conclusion: It’s clear that switching is always a better option since \(2/3 > 1/3\).

Why people get it wrong

Some people mistakenly assume that some sort of new game begins once Monty Hall reveals one of the doors. It gives the impression of a “fresh start” with only 2 doors. This complete disregards “prior knowledge”. It’s tricky because we are not used to think about sample spaces and conditional probabilities in our daily lives but when we consider carrying over the prior knowledge we see a beneficial path in many situations involving chance. This seems to be true for life in general.